The early years

At the end of the 19th Century many refugees from persecution in Russia came to Britain. Hannah Frank’s father was one of these, and settled in Glasgow in the early years of this century. Glasgow at the time was one of the world’s most prosperous cities whose products were universally admired. It was also an international port, and thus it is not surprising that such a place should attract artists and craftsmen from all over Europe.

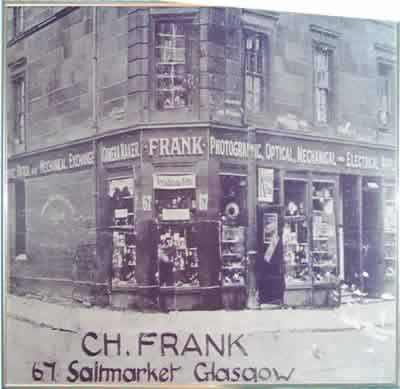

Charles Frank settled in the Lauriston district of the Gorbals, where he began business as a master mechanic. After a few years he married another immigrant, Miriam Lipetz, and eventually opened a shop at 67, Saltmarket for the design, sale and repair of photographic and scientific apparatus. Over the following half-century it was to become one of the best-known

photographic centers in the city.

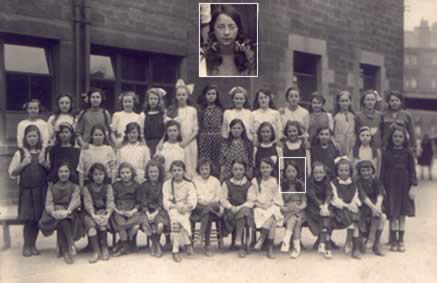

Hannah, one of four children, was educated at Strathbungo School, Albert Road Academy and the University of Glasgow, where she graduated in Arts in 1930. She had a number of poems, and later a series of drawings, published in the Glasgow University Magazine, all of which appeared under the name Al Aaraaf.

What is the

significance of 'Al Aaraaf'?

Hannah Frank signed many of her early drawings ‘Al Aaraaf’. This is the title of a long poem by Edgar Allan Poe which had special significance for the young Hannah Frank. It was the name given by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe to a mysterious star which suddenly appeared in the heavens, and after growing brighter and brighter for a few days, suddenly disappeared, never to be seen again.

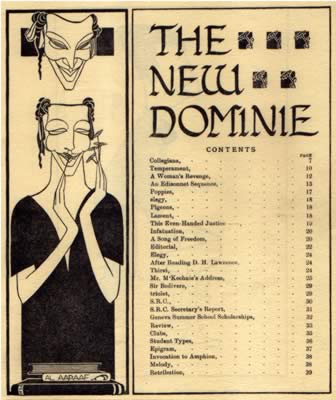

After attending Jordanhill Training College, where she contributed drawings to the New Dominie, she taught for a number of years, principally at Campbellfield School in the east end of the city.

During all this time she attended evening classes at Glasgow School of Art, widening her interests to include wood engraving for which she was awarded the James McBey Prize.

From 1930 to 1950 her drawings appeared regularly at the Royal Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts exhibitions.

Sculpture at the Glasgow School of Art

In 1939 Hannah married Lionel Levy, a mathematics and science teacher whose expertise was to prove invaluable when she came to take up sculpture.

This she did at the Glasgow School of Art where she took up clay modelling under Paul Zunterstein and met the genial Benno Schotz who encouraged her to concentrate on that form of art.

Since the early 1950’s she has worked solely in this medium, exhibiting at the Royal Glasgow Institute and the Royal Scottish Academy. There have also been exhibitions at Stirling University, the Portico Gallery, Manchester, and as part of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe.

Contributions to the Jewish Community

Hannah and her husband Lionel Levy were active members of the Glasgow committee of the Friends of the Hebrew University, and she contributed sculptures and drawings to their fundraising appeals.

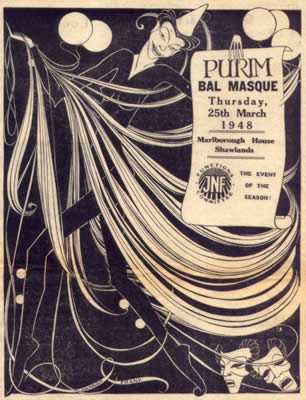

In the 1940s she provided illustrations for various Jewish organisations, and throughout the 1980s and 1990s her drawings were used to illustrate the Scottish Jewish Archives newsletter.

The Drawings

Hannah Frank’s drawings have a strange indefinable quality all of their own. Considering their poetic inspiration, it is not surprising that many express a pensive melancholy. Others however are filled with sunshine and youthful exuberance, set in that garden of the world’s innocence already echoed in the mediaeval romanticism of Burne Jones. But there are also menacing night scenes fraught with fear and sinister foreboding. In such an atmosphere death seems to be never far away.

The elongated figures with their long flowing tresses belong to the world of the Macdonald

sisters and Jessie King. There are inevitably echoes of Aubrey Beardsley who has influenced every artist working in black-and-white since the beginning of the century. The cloaks, richly embroidered with flower motifs may also owe something to the sinister creations of the Irishman, Harry Clarke. They are a special feature of the series of illustrations of the Rubaiyat. Other drawings such as ‘Garden’ seem to belong to the world of the Scottish artist, John Duncan.

But Hannah Frank’s world is very much her own, and quite unmistakable. The drawings have an austerity and stylisation not to be found in the works of other artists, particularly effective where there is a dramatic contrast with white bodies against a dense black background.

The Sculptures

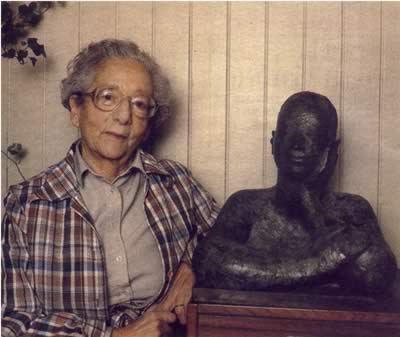

The latest drawings are dated 1952, and it is at that time that the earliest sculptures appear. They are mostly figure studies, in plaster, terra cotta, or bronze, and all on a fairly small scale. The influence of Henry Moore as well as Benno Schotz and Paul Zunterstein can be seen in some of them but, as in her drawings, she has evolved her own personal style.

Portraiture has formed only a small part of her work, a fact to be regretted when one sees the quality of the heads she has done, particularly that of her father.

The sculpture has been exhibited at the Royal Scottish Institute since 1954, and also at the Royal Scottish Academy and the Royal Academy.

It has found many admirers, notably in Sydney Goodsir Smith, who wrote when reviewing an R.S.A. Exhibition in 1965 — “Sculpture in Scotland, for long the Cinderella of the arts, due largely to historical and religious causes, seems to be slowly rising up out of the slough of despond and getting better and stronger, more imaginative and creative. The great difficulty facing this profession is dearth of opportunity … Hannah Frank’s voluptuous ‘Reclining Woman’ is classical in her ease of pose and perfect calm, a lovely wee thing”. On another occasion he had drawn attention to — “…one of the most covetable small pieces is a tiny green bronze, ‘Woman Resting’, by Hannah Frank”.

Exhibitions

A retrospective exhibition took place in Glasgow in 1983 to celebrate her 75th birthday.

In 2002 her work was shown at the Peter Scott Gallery at Lancaster University, and in 2003 there was an exhibition of her drawings at the Gregson Centre, Lancaster. The Lancaster connection comes from her niece, Fiona, who lived and worked in the city.

A five year international tour took place between 2003 and 2008, visiting England, Scotland, and several venues in the US, and culminating in a centenary exhibition at the University of Glasgow opening on her 100th birthday, 23 August 2008.

Hannah Frank died in December 2008 in a care home in Glasgow, where her drawings and sculpture are still on show and are much admired by residents, staff and visitors. Exhibitions of her work continue to be held, contact Fiona Frank for information.